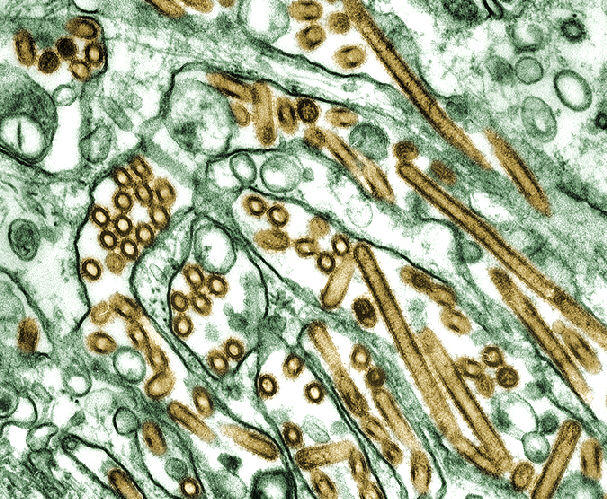

| Next flu pandemic: What to do until the vaccine arrives? Scientists call for more study of routine preventive measures during annual flu season. |

"These are ironically similar to the measures used in 1918 to combat the greatest of all known influenza pandemics, but there's a lot we don't know about what may very well be our best defenses," says lead author Stephen Morse, PhD, associate professor of Clinical Epidemiology in the Department of Epidemiology at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health. According to Dr. Morse, unfortunately, there are no readily accessible compendia of best practices or even comprehensive databases of community epidemiologic data, which might help to design the most effective interventions. "As the weather turns cold and the regular flu season is upon us, there is an opportunity to prepare and move ahead with community studies and clinical trials in humans."

How influenza is transmitted, from person to person, whether by large droplets or by fine particles, may seem to be a specialist issue, observes Dr. Morse, but "it has a direct bearing on how far apart people should position themselves to prevent infection and on whether inexpensive face masks might be useful."

Dr. Morse's coauthors are Richard L. Garwin, PhD, IBM Research Laboratories and Paula J. Olsiewski, PhD, of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. This spring, the authors organized a workshop on personal and workplace protective measures for pandemic influenza held at the Mailman School of Public Health and funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

"There are many basic things we don't know about how influenza is transmitted," said Dr. Garwin of IBM. "For example, it appears that a relatively low number of people catch the flu from another person. Breaking the transmission chain with non-pharmacological measures has proved challenging, but the prize is enormous."

Often also neglected, according to the authors, are protective measures that fall between individual protection and the whole population -- "the excluded middle"-- such as buildings, facilities and smaller areas such as work places and homes. Examples might include improved air-handling systems, room-size fans, portable air-filtration systems, or physical barriers such as room dividers and doors.

"We should systematically address knowledge gaps now during upcoming flu seasons rather than wait to empirically test measures ad hoc when the next pandemic is upon us," says Dr. Morse. ###

Contact: Stephanie Berger sb2247@columbia.edu 212-305-4372 Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health

Technorati Tags: 1918 Pandemic and Influenza Virus or CDC and Pandemic and Avian influenza or Bird Flu and H5N1 or adenovirus and recombinant or vaccines and Epidemiology